Pancreatic cancer lands like a punch you didn’t see coming. It scrambles plans and steals breath. People want straight talk, not sugarcoating. They want to know what’s happening inside the body, and when. They want a path that feels real.

A doorway into the bloodstream

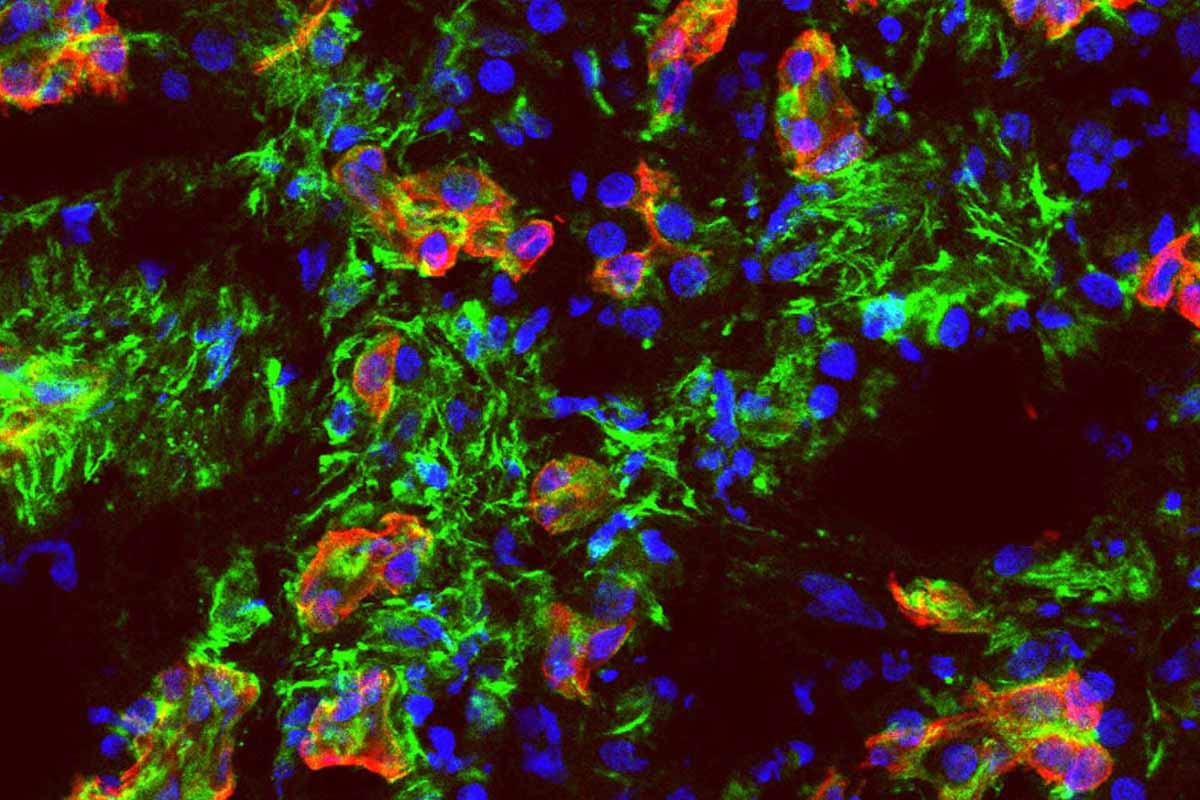

A Cornell-led team finally mapped how this disease slips into circulation. That’s the moment it turns scary, because once tumor cells ride the blood, they can seed new sites fast. The group zeroed in on a receptor called ALK7. Flip it on, trouble starts. Turn it off, the spread slows. Their experiments weren’t just petri dishes and hope. They used mouse models and clever organ-on-chip systems that mimic human vessels. In those tiny channels, researchers watched cells behave like they would in us. When ALK7 was blocked, cells struggled to enter the vessel wall. That’s where you want to win. One early gate, held shut. It won’t cure pancreatic cancer, yet it targets a precise step that fuels metastasis.

Pancreatic cancer

Let’s talk about the armor wrapped around these tumors. The microenvironment is dense and fibrotic, almost like scar tissue poured into concrete. It should stop escape. It doesn’t. That paradox has haunted labs for years. If the wall is so thick, why do cells move so easily? The answer sits in two coordinated pathways triggered by ALK7. One pathway pushes cells through an identity shift called epithelial-mesenchymal transition. They loosen their bonds, change shape, and learn to crawl. The other pathway prompts the release of enzymes that chew at vessel walls. You get both motive and means. A tank with a cutting torch. That’s why spread seems so fast in a cancer already boxed in by tissue.

The numbers behind the fear

This disease carries brutal statistics. Fewer than one in ten patients reach five years after diagnosis. Families feel that number like cold wind through a cracked window. It changes conversations at kitchen tables. Screening is tricky, symptoms often hide, and treatments fight uphill. That’s why a precise target matters. When the study blocked ALK7, metastasis slowed in animals. The organ-on-chip work added something rare: visibility into the exact moment of invasion. Researchers could test whether cells invade vessels first or exit them later to seed organs. When they put cells outside the vessel and blocked ALK7, entry stalled. Put them inside the vessel, spread resumed. Timing was the lever. Hit the switch early, you get traction. Miss it, you’re chasing shadows. In that narrow window, pancreatic cancer shows a softer underbelly.

What ALK7 really means for care

We’re not talking miracle talk. We’re talking a clearer target and a sharper moment to act. ALK7 sits like a foreman on a busy job site, waving cells forward and breaking ground on the vessel wall. Stop the foreman, the crew stalls. That reframes a long argument in the field. Some papers linked this receptor to blocking spread.

Others blamed it for accelerating it. This study helps sort the mess. Context matters. The microenvironment and the disease stage change the story. In early invasion, ALK7 looks like a driver. That points to therapies aimed before cells cross into blood. Picture a drug that keeps those gates shut. The organ-on-chip system helps test that idea with speed and clarity. It isn’t a replacement for people. It’s a rehearsal stage that looks and behaves like the real set. You can tweak lighting, timing, and cast, then carry the best cues forward. If that line of work holds, patients might see smarter trials and fewer dead ends for pancreatic cancer.

Catching the window, changing the odds

There’s a small window where choices echo. That’s true in medicine, and it’s true in life. The study suggests that blocking ALK7 early limits the first step of escape. Once cells circulate, they’re travelers with many exits—lungs, liver, wherever blood flows and luck runs bad. Early blockade won’t fix everything, yet it can blunt that first breakaway. That insight shapes strategy. Clinicians could watch for markers tied to ALK7 activity. Engineers could refine chips to mirror patient-specific vessels.

Biologists can dig into the two pathways and find weak links. Every thread creates room to maneuver. I think of families reading a report like this and feeling two emotions at once. Relief, because the map finally shows a door you can lock. Restlessness, because the lock needs a key you can hold soon. Research moves at a measured pace. People don’t. Still, this is momentum you can feel. It puts real language to a hidden act—cells entering blood—and tells us where to stand and block the way. It also opens doors to studying other cancers, or how immune cells pass in and out of vessels when they hunt. New chips, new questions, better tests. That’s how the line moves. That’s how we shave risk, inch by inch, for pancreatic cancer.

The armor, the engine, the tools

Let me stitch it together once more. The tumor sits inside tough, fibrotic armor. You’d think that armor ends the story. ALK7 changes the script by launching two moves at once. Cells gain mobility through EMT, then summon enzymes to cut through vessel walls. The team watched it live on vessels built in the lab, then confirmed the pattern in animals.

Block the receptor early, and the first breach falters. Wait, and cells already in the bloodstream drift and settle elsewhere. That’s why timing matters so much here. It turns a mystery into a plan. Not a perfect plan, but one the field can use. Behind every pathway chart, there’s a person waiting for options that feel human. Fewer buzzwords. More clarity. More days at home. If this work keeps its promise, care teams might get a handle on the very first leap, and keep it from happening at all. That won’t erase the fear, yet it gives you a grip. And sometimes, a good grip is enough to breathe again with pancreatic cancer.